Leading AlzheimerŌĆÖs theory survives drug failure.

Solanezumab flopped in a large clinical trial, but the drug or others like it could yet succeed.

A drug that was seen as a major test of the leading theory behind AlzheimerŌĆÖs disease has failed in a large trial of people with mild dementia. Critics of the ŌĆśamyloid hypothesisŌĆÖ, which posits that the disease is triggered by a build-up of amyloid protein in the brain, say the results are evidence of its weakness. But the jury is still out on whether the theory will eventually yield a treatment.

Proponents of the theory note that the failure could have been due to the particular way in which solanezumab, the drug involved in the trial, works, rather than a flaw in the hypothesis. And other trials are still ongoing to test whether solanezumab ŌĆö or other drugs that target amyloid ŌĆö could work in people at risk of the disease who have not shown symptoms, or even in people with AlzheimerŌĆÖs.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm extremely disappointed for patients, but this, for me, doesnŌĆÖt change the way I think about the amyloid hypothesis,ŌĆØ says Reisa Sperling, a neurologist at the Brigham and WomenŌĆÖs Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. She is leading one of several trials to test whether drugs that aim to reduce the build-up of amyloid ŌĆśplaquesŌĆÖ can prevent AlzheimerŌĆÖs in people at risk of the disease.

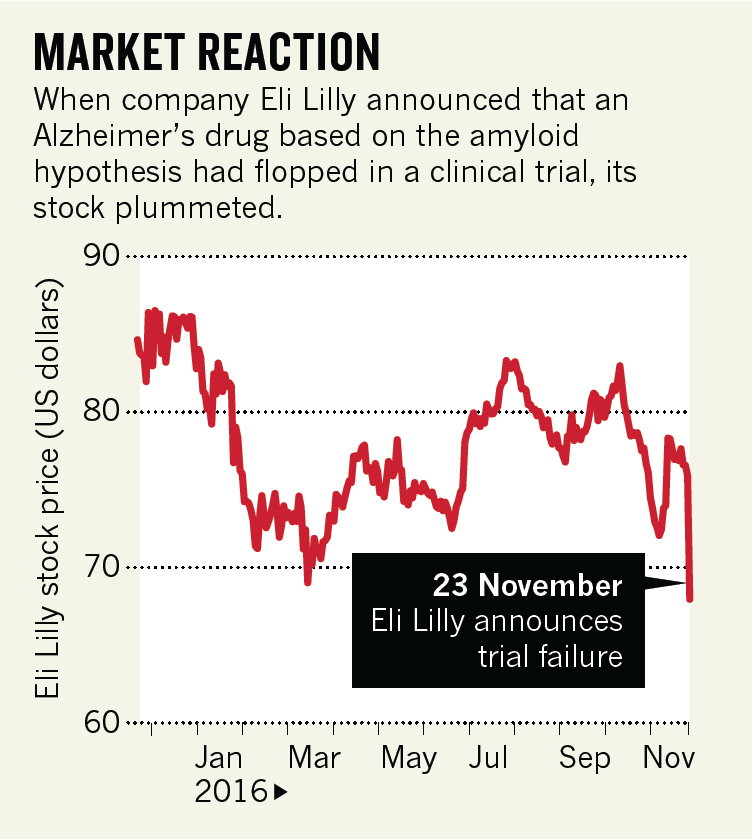

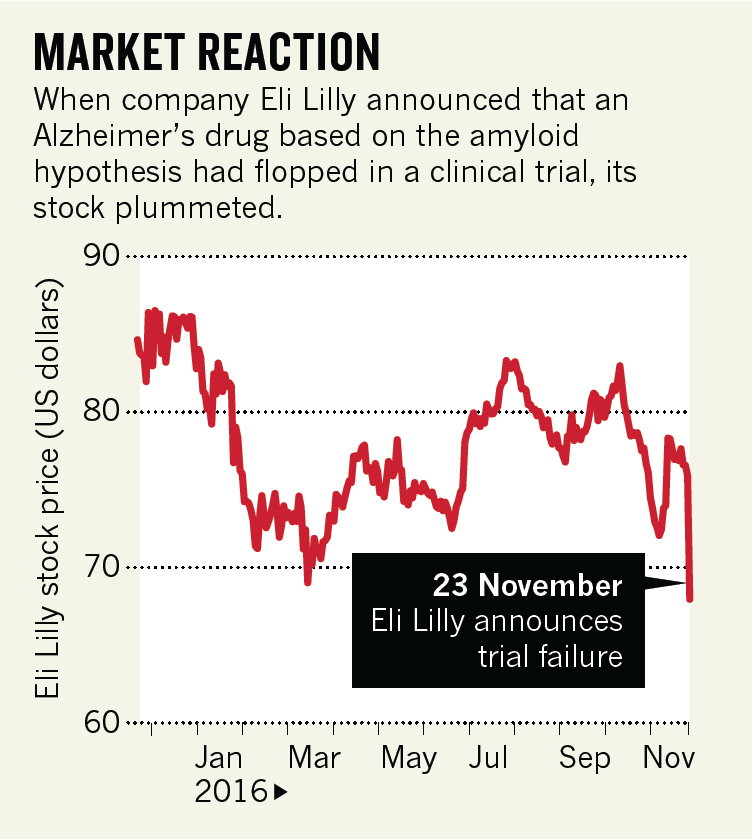

Solanezumab is an antibody that mops up amyloid proteins, which can go on to form plaques in the brain, from the blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Eli Lilly, the company that developed the drug, announced on 23 November, 2016 that it would abandon it as a treatment for people with mild dementia.

The outcome adds to a long list of promising AlzheimerŌĆÖs drugs that have flopped in the

clinic, many of which, like solanezumab, targeted amyloid.

The Lilly trial tracked more than 2,100 people diagnosed with mild dementia due to AlzheimerŌĆÖs disease for 18 months. Half received monthly infusions of solanezumab, the other half a placebo. Analysis of people with comparable symptoms in earlier studies of solanezumab had seemed encouraging, but the latest trial indicated only a small cognitive benefit, not enough to warrant marketing the drug (see ŌĆśMarket reactionŌĆÖ).

PREVENTION HOPE

Lilly has also been running prevention trials to see whether solanezumab might help people at especially high risk of the disease. The company says it will now discuss with its trial partners whether to continue with those.

SperlingŌĆÖs trial is one of these, and tests solanezumab in people who have elevated amyloid levels in the brain but have not shown any symptoms of dementia. Researchers at Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, are also testing solanezumab, and a similar antibody made by drug company Roche, in people who are currently healthy but are genetically at high risk of developing AlzheimerŌĆÖs. Meanwhile, the Banner AlzheimerŌĆÖs Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, is testing the effects of three therapies that target amyloid production, one of which is an antibody, in people at high genetic risk of AlzheimerŌĆÖs.

The Lilly outcome ŌĆ£doesnŌĆÖt disprove the amyloid hypothesis, and it really increases the importance of these longer prevention trialsŌĆØ, says Eric Reiman, the Banner instituteŌĆÖs executive director and leader of the trials.

LillyŌĆÖs result may say more about the characteristics of solanezumab than about the accuracy of the underlying amyloid hypothesis, says Christian Haass, head of the Munich branch of the German Centre for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The antibody targets soluble forms of amyloid, he points out, so it ŌĆ£could be trapped in the blood without ever reaching the actual target in the brain in sufficient quantitiesŌĆØ.

Biogen, a company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is testing a different antibody called aducanumab, which targets amyloid plaques in the brain. In early clinical testing, the antibody showed signs of clearing amyloid and alleviating memory loss in people with mild AlzheimerŌĆÖs disease; results from phase III trials are expected in 2020.

ŌĆ£Until the aducanumab data read out, we have not truly put amyloid to the test,ŌĆØ says Josh Schimmer, a biotechnology analyst at financial services firm Piper Jaffray in New York City.

Still, the negative trial findings have emboldened critics of the amyloid theory, who are weary of its failure to yield a treatment. ŌĆ£The amyloid hypothesis is dead,ŌĆØ says George Perry,a neuroscientist at the University of Texas at San Antonio. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs no sign of anybody getting better, even for a short period, and that suggests to me that you have the wrong mechanism,ŌĆØ adds Peter Davies, an AlzheimerŌĆÖs researcher at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York.

No matter what Lilly decides about its other solanezumab trials, the company isnŌĆÖt giving up on AlzheimerŌĆÖs. It is testing an inhibitor of an enzyme involved in the synthesis of amyloid in partnership with AstraZeneca, and is progressing with a handful of candidate therapies aimed at other targets.

Source : NATURE Magazine - December 1, 2016